Cooler cities for a hotter future

As climate change intensifies, cities must blend nature-based and technological solutions to remain liveable.

As global temperatures rise, urban areas must evolve to protect residents – particularly the most vulnerable.

Climate change and rising urbanisation are making heatwaves more frequent and fierce, thanks in part to the urban heat island effect.

This effect sees cities becoming significantly hotter than their surroundings due to the asphalt, concrete and buildings that absorb and retain heat.

The prevalence of extreme heat in Australian cities is currently under-reported due to gaps in weather data, according to a recent Western Sydney University study, with temperatures above 35 degrees Celsius far more common across parts of Greater Sydney than official weather stats indicate.

With extreme conditions predicted to occur more frequently and last longer in Australia and around the world, some groups are disproportionately affected as the mercury rises, including disadvantaged, socially isolated, and older people, meaning an aging population will only add to the pressure to find new ways to stay cool.

So what's been shown to break the heat cycle in urban environments? Here are just some of the ways forward-thinking cities are building climate-resilience.

Tree power

The urban heat effect means cities are often much hotter than their surroundings, resulting in higher temperatures and also exacerbating global warming.

Increasing tree coverage is one of the simplest and most effective cooling solutions. But how many trees are enough? Dutch urban forestry expert Professor Cecil Konijnendijk introduced the following 3+30+300 rule in 2022 as a guideline:

• Can you see three trees from your home, school, or workplace?

• Does at least 30% of your neighbourhood have tree canopy cover?

• Is there a park within 300 meters?

While this standard is still relatively new in Australia, it's gaining global traction, according to Thami Croese, Research Fellow at RMIT University’s Centre for Urban Research.

In a study of eight leading cities – Melbourne, Sydney, New York, Denver, Seattle, Buenos Aires, Amsterdam, and Singapore – only Singapore met the 3+30+300 rule on all three counts.

The city-state boasts 78 square kilometres of green space including its Bay South garden which boasts colossal solar-powered supertrees (pictured above). Also, all new public housing must include greenery in the form of green roofs, foliage walls or hanging gardens.

“We found canopy cover in desperately short supply, even in some of the most affluent, iconic cities on the planet," Croese said. "Better canopy cover is urgently needed to cool our cities in the face of climate change.”

So how much difference do trees make? According to a 2023 study led by Tamar Iungman at the Barcelona Institute for Global Health, average tree cover in European cities is just 15%, but increasing this to 30% can lower temperatures by 0.4°C, with a maximum effect of 5.9°C in some areas, and reduce heat-related deaths by 40%.

Green roofs

Green and garden roofs not only keep cities cooler, they also lower building energy demands, absorb rainwater, improve air quality, support biodiversity, and create aesthetic, relaxing spaces for urban dwellers.

Skovbrynet Basecamp, an innovative housing concept built in 2020 in the Danish city of Lyngby (pictured), is a great example of this trend. Park-like gardens dotted with trees, plants and trails cover the curvy building, with residents and visitors able to hike up to the sixth floor and experience lake views.

Closer to home, Australian company Fytogreen, which specialises in urban ecosystems, has implemented some notable green roof projects, including:

• A 10,000-plant green roof at the University of Tasmania’s new campus, offering a natural refuge for wildlife

• A roof garden at Watermans Cove in Barangaroo, enhancing Sydney’s foreshore with cooling greenery

Solar car parks

Large, asphalt-covered car parks are major heat generators in cities. Car parks in western Sydney alone cover six square kilometres – an area equivalent to 840 soccer fields of heat-absorbing asphalt, according to Western Sydney University researcher Dr Sebastian Pfautsch.

“In a warming world, improving the design of new and existing car parks is essential. Regulations and guidelines need updating. Shadeless, heat-radiating car parks must become relics of the past. We have the necessary technology. We don’t need to wait. We need to change.”

Some solutions include:

• Using reflective and porous materials to replace heat-absorbing asphalt

• Increasing tree canopy and integrating shade structures

• Installing solar panels as car park roofs to provide shade and generate renewable energy

A recent study by the Australian National University found that covering 60% of Australia’s large outdoor car parks with solar panels could, in addition to providing shade, generate 12.3 gigawatts of capacity and 34 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity annually.

Three years ago France passed a law requiring parking lots with between 80-400 spaces must be covered with solar panels, and operators have until July 2028 to be in compliance.

One of the early movers in solar carparking in Australia is Adelaide's Elizabeth City Centre which has shaded 1,400 car spaces with solar panels.

Parkland structures

Innovative parkland structures can provide natural cooling, according to Princeton University researchers who are developing low-cost, scalable cooling solutions for greenspaces to be tested in New Jersey, where Princeton is located, with a view to rolling them out around the US. These solutions include:

• Misters that provide evaporative cooling to lower air temperatures

• Wind-control fabric structures, inspired by kirigami, that help direct breezes into urban spaces

• Cooling panels containing cold water pipes and covered in humidity-repelling membranes to absorb body heat

• Retro-reflective coatings on surfaces to bounce heat away

• Sun sails that reflect heat away from people and surrounding structures

Cooling paint

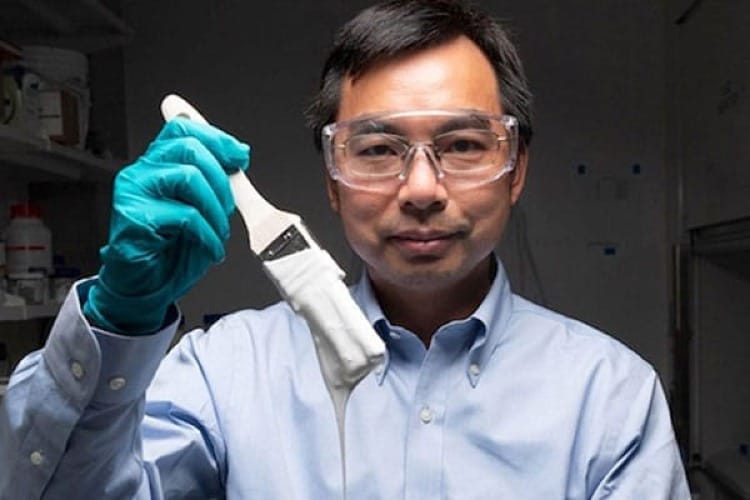

The whitest paint on record, designed to reflect 98.1% of solar radiation while also emitting infrared heat, has been developed by researchers at Purdue University. By reflecting more heat than it absorbs, surfaces coated with this paint can cool below the surrounding temperature without using electricity.

“When we started this project about seven years ago, we had saving energy and fighting climate change in mind,” Professor Xiulin Ruan of Purdue University said. The research team is now working with a paint company to develop the paint into a commercially viable product.

One downside of cooling paint, however, is that it works so well it can increase the need for heating in the colder months. With this in mind, architectural engineer Hassan Khan and colleagues at UNSW have been working on a new approach.

By adding a fluorescent coloured film on top of the white paint materials they were able to reduce glare and also improve year-round energy efficiency.

These materials are known as passive-coloured radiative coolers, and several colour configurations using orange, red and green were found to have similar cooling effects to their white counterparts without requiring more heating in winter.

Cooling centres

With extreme heat becoming more common, cooling centres – air-conditioned public spaces like libraries and auditoriums – are on the rise. However, vulnerable groups, such as the elderly, the disadvantaged, and the socially isolated, often struggle to access them.

To address this issue, Arizona in the US is rolling out COOLtainers – solar-powered, air-conditioned shipping containers located in convenient places that are open on weekends and during power outages.

Nearly 20 of these mobile cooling centres – which each house a TV, wifi, games, snacks and even a place to snooze – are being deployed across the state to assist communities in need as part of Arizona's Extreme Heat Preparedness Plan.